Forgive me, I'm a total movie person, so I'm about to geek out pretty heavily on the subject of Blade Runner.

So I was reading something by Philip K. Dick (This, actually) and suddenly, on a whim, decided to watch this "Science-fiction masterpiece" again. Now I already had very specific ideas and opinions about this movie, mainly about how much I hated it. It was slow, it was talky, it pretended to be Noir, but really wasn't, it pretended to be a mystery, but was really just a stupid action movie. Not to mention whenever anyone talks about it, all they can do is say how groundbreaking the special effects are. Not the plot, not the acting, not the ambition of ideas, not the reinvention of science-fiction priorities, just the special effects. 5 years after George Lucas dropped the weak-assed-plot-wrapped-in-eye-candy Star Wars, all people could talk about was how pretty the lights looked on the screen. But that's the whole thing. After watching Blade Runner again, I realized that the visuals (even by Star Wars standards) are okay, but the true merit of the film lies somewhere in the real meaning behind the movie, and not the movie itself.

For those unfamiliar who might still be reading, I have to spoil a part of the film to really talk about what I find interesting. The film involves androids who are true mock-ups of humans and only differ from us in that they cannot feel emotions. However, since the computers are so advanced, there is a theory that they can develop emotions naturally, and the androids in the film truly do. A set of four escape from a mining planet and sneak back to Earth (where they are illegal), and set out killing those who work in the company that actually built them.

Perhaps you're wondering why they're killing their makers, and I'm pretty sure I wondered this every time I watched it. Why would you want to kill your creator? What did he ever do but give you life, the ability to experience everything you do, every flower you smell, every steak you taste, every moment you ever live through can be sort of traced back to your creators responsibility (other than yourself, really [this isn't necessarily true with humans, but as an android, it is more so]. So why the hell would Roy Batty want to take on his creator?

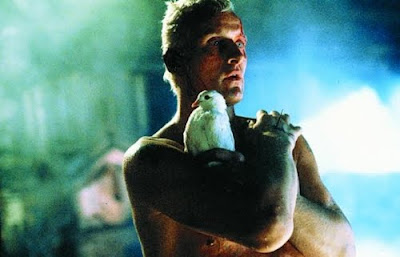

Well, you see, Replicants (their name for the androids [assuming because the word Droid is Copyrighted by Lusafilms LTD. Really, go look at an add for the new Verizon smart phones and read the tiny print) can only live for four years. So he does what anyone would do when they find out they have a limited existence: he flips the fuck out. He tracks down his creators, kills them one by one, and then finds his "father"--the president of the Tyrell company--and drives his thumbs into his eyes while simultaneously crushing his skull, after it is revealed that he only has 4 years--no more.

Perhaps this seems a bit reactionary--after all Tyrell did nothing but create robots and make a slaying in the profit margins (to the point where he has God-like control and monopoly over the creation of fake people). But that's the catch, isn't it? Because Tyrell didn't create fake life--he created a consciousness that might one day learn emotions and can handle complex problems and fake a human life pretty easily. So in effect, Tyrell created non-biological life. But as an adult, shouldn't Roy Batty go through the normal 5-step process that most adults go through when confronted with grief? Well, no, after all, he's only 4. He is more intelligent, sure, than a 4 year old, but he hasn't reached an emotional capacity beyond anger, as revealed to us when he kills everyone he comes in contact with. Not only this, but he was built logically, his consciousness was built upon ones and zeros--the ultimate logical plane. So now that emotions have been developed after time, it throws those ones and zeros out the windows, or at the very least scrambles them quite a bit. So his only natural response is to kill and destroy.

[Stephen King Moment] Also, In Pet Semetary, Ellie, the oldest daughter, reacts pretty angrily when she finds her pet cat Church has died (based on a real reaction of SK's daughter when her own cat died) throws a bit of a temper tantrum (I think SKs daughter smashed some stuff in the garage), screaming "Church was my cat, let God get His own cat!" Showing even little girls don't react very well when the tenents of mortality leap up and smack us in the face. [/Stephen King Moment]

But what does that say about us? If you went to God tomorrow and said, "Look man, this Heaven place seems fine and dandy, but I'd really like a couple more years down there--I've got some shit to take care of. After all, I never made it to Ireland, I never found a woman to share my life with, I never got to see a live football game, etc," and he said "Sorry, Mate, but I've got bigger shrimp on the barbie than you," (for some reason God is Paul Hogan of Crocodile Dundee II fame in my fantasies), I'm pretty sure I'd be pissed. Maybe not drive-my-thumbs-into-your-eye-sockets-while-simultaneously-crushing-your-skull pissed, but maybe spray-paint-your-car-like-a-wife-with-an-adulterous-husband pissed.

I guess the only real difference is that Tyrell, in his god-status to the replicants can't give everlasting life (or hell, a new battery) to Roy Batty, the story with us and God is...well, what exactly? That he won't? That we won't need it? That maybe he can't? The ambiguousness is the real lesson, as it usually is when Science Fiction takes on religion.

Anyway, these aren't my concerns (I'm cool with my beliefs as they are and aren't), but these are the concerns of the film, and somehow on this last viewing, I finally saw it. Wikipedia says this movie is multi-faceted, and I can buy that, but usually there are movies out there that mean nothing to me upon frequent viewings and then suddenly POW I get it like a lightning strike through my head, and I get the way I can think about the movie in a new way that makes it interesting whereas before it was shitty. Now if I could only do that with The Departed, I can die happy.